20th-century masterpieces

Written by Susanne van Els,

General Director Opera at Maastricht Conservatory

This article is an editing of a program at a concert by the orchestra of the Maastricht Conservatory (November 2016)

The music of Stravinsky, Weill and Messiaen.

Is that modern music? Not exactly, a newspaper from 1920 only contains old news.

So, is it new music? Well… it was, back then. As was Mozart’s music, 250 years earlier. And Bach’s music too, literally unheard-of!

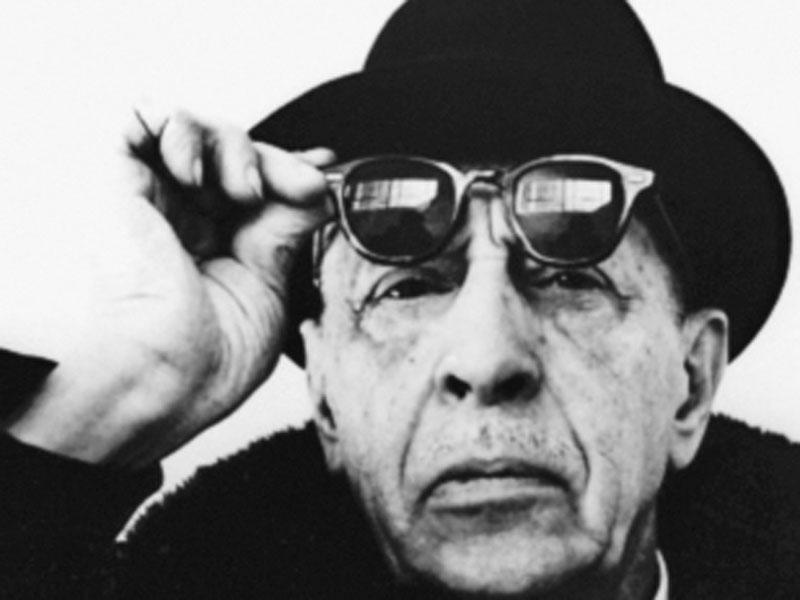

But The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky (the cosmopolitan born in St Petersburg to Ukrainian parents, whose Ballets Russes caused a furore in Paris, who stole the show on the American West Coast and at the White House, and was buried in Venice), isn’t that a very difficult piece?

Music is an extraordinary phenomenon

Our ears are trained to interpret sounds quickly: they can filter out the hum of voices during an interesting conversation in a pub, but a low thudding sound, no matter how soft, immediately alerts the brain to danger. We can ‘stop listening’ but ‘not hearing’ (unlike closing your eyes) is impossible. We all have a well-developed sense of hearing that can determine very quickly what is what, and it all ends up in a vast database: the ear has incredible associative power. That is the basis of our musical susceptibility.

Through the centuries, music has had all kinds of social and ritual functions. At noble moments, but also when the masses needed to be stirred up, or an army pushed forwards: music did its job. And then Bach started composing for the sake of composing. Although he too wrote mainly on commission or for special occasions – a few complete church annals, a cantata for the inauguration of the local council – at some point he decided to write an additional étude for his harpsichord students because he wanted to complete the cycle, because constructing another fugue on a yet more complex theme presented a challenge. Classical music entered into a dialogue with itself. Each new piece related to the previous one, the surprises, the inventions, the colours, the structures and the stories. Music started its own history.

Time after time something new

Did you know that the audience Mozart depended on for his income refused to listen to a piano concerto that was six months old? They demanded a premiere! And that is only natural: artists are the ultimate children of their time, they build on what is there already and want to add something new. Many young musicians who write their Opus 1 at the age of thirteen stop being creative as soon as they get acquainted with everything that is already there – by definition, to make something is to create something new, something original. Artists climb onto the shoulders of giants from (musical) history and take a good look around, at their own time.

Multiple layers

Classical music, then, has multiple layers of meaning: music ‘does something’ to us all, because of our susceptibility to sound and the associative power of everything we hear, and music also relates to other music – or as Stravinsky put it: “Music expresses nothing but itself.” What he meant by that is not that music is meaningless, or without effect; he was trying to explain the huge power of expression that classical music has, as the most absolute of all human expressions.

But what about this 20th-century or contemporary music that is so hard to listen to, or even unbearable?

Back to Mozart: in every composition, in every phrase, he takes us by surprise. Never, ever, did Mozart write the obvious. He was ingenious and always looking for new inventions. His music touches us, it feels as if a friend is talking to you, as if a lover is confiding in you. But his contemporaries were often taken aback by all those new sounds and notes! And do we not, after all those centuries of getting used to them, only hear the outside, which sounds harmonious to our ears, instead of the sting, the dissonants, the silly pranks and the hidden delights?

When Beethoven presented his Opus 59 to his patron Count Razumovsky, he thought the composer was playing a poor joke on him by coming up with such a ridiculously unplayable score, with such an inimitable form and such puzzling harmonies. “This isn’t music”, the musician/patron exclaimed…

Equally great strides as those by Mozart and Beethoven were made by Stravinsky, who, after all, was also a brilliant composer. His century, though, was one of great horrors and huge social changes that were perhaps less promising than the Enlightenment of his predecessors. His music reflects that.

Multiple dimensions

Another thought: nearly all the musicians on stage once played these pieces for the first time. They knew the music, had learned about it and listened to it. And to them, a piece like Symphonies for Wind Instruments was new music. As it might be for the majority of the audience. And because it is good classical music, well-written according to previously established principles (new! and in relation to all that other strongly abstract art), it has multiple dimensions. Your ear is not familiar with the sounds of this composition and needs to interpret them, add them to the repertoire – and precisely because Stravinsky created something unique, that is quite an effort. But this is an effort that will pay off: music, after all, is capable of being a very accurate expression of its time while at the same time harbouring timeless human observations. Actually, classical music has always been more about truth than about beauty…

As a violist, I was fortunate enough to work with the giants of our own time: I played the Dutch premiere of György Ligeti’s Sonata for Solo Viola, I recorded CDs of Mauricio Kagel’s work, conducted by the composer, just as I did with John Adams and Steve Reich, and I worked with György Kurtag. During my music studies, we did projects with John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Olivier Messiaen. Great composers, including Louis Andriessen and Willem Jeths, wrote pieces for me. Etcetera.

Working with composers, learning to understand how they listen, what they look for, being able to act as an ambassador and advocate of their notes among my contemporaries, taught me a lot about my great love, Mozart. With that same interest and amazement, I look at what he created, try to see how he goes against expectations, how he plays tricks on our ears and challenges our musicality, and I try to imagine the impact his music must have had in his day.

Being receptive to new discoveries

Every piece is discovered every time it is played, by the musicians and audience together. By listening together, we experience something, something with multiple dimensions: a familiar and beautiful piece is recognised and dusted off, cherished. A new piece is uncharted territory for the ear, making it more difficult and confusing, but when we wake up the next morning it leaves us feeling like we have experienced something rather special.

I heartily invite you to open your ears and hearts to the music of composers like Stravinsky, Weill, and Messiaen. Just listen and enjoy, without worrying about ‘knowing’ what it is you are hearing, or worse, what you should be hearing!

Open all your senses, and observe your own responses.

Susanne van Els

General Director Opera at Maastricht Conservatory